|

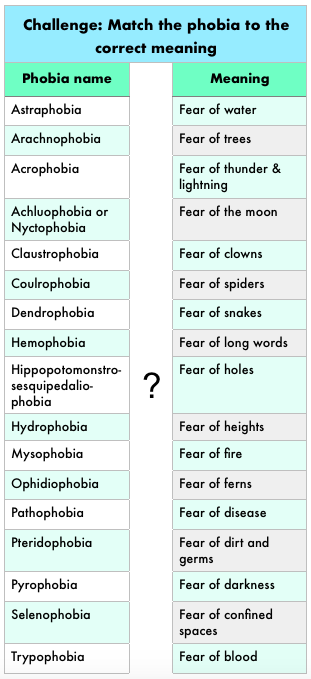

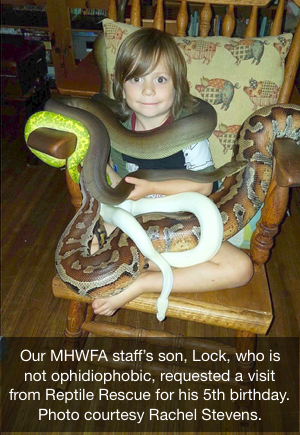

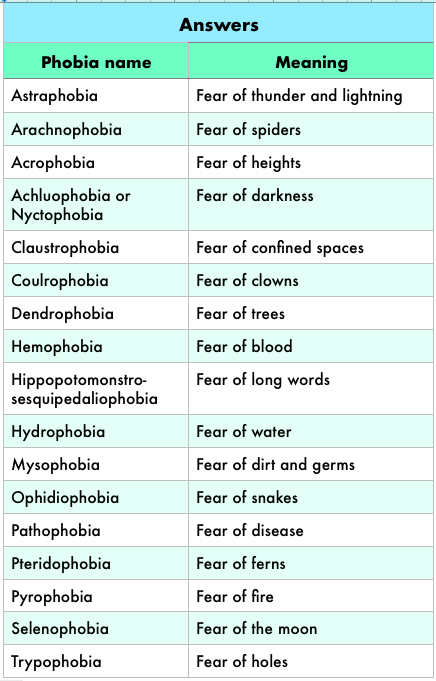

“S-s-s-SNAAAAKE!!” The terrified cry came to me from across the campsite where, on the Juan de Fuca trail, I had been guiding a family hiking trip for the past three days. Adrenaline surged through my body and my pulse skyrocketed in response to the emotion in the scream, which turned quickly in to a frantic, high-pitched sob. Before our expedition began, Gabrielle, a high-functioning mom and legal professional from Vancouver, had indicated a strong fear of snakes on her medical form. “I know they’re not poisonous out here,” she wrote. “I can’t help it. If you see a snake, please don’t tell me.” Now, one had suddenly appeared close to her. My muscles tensed as my brain prepared my body to run to her aid. Specific phobias are not uncommon, either in the wilderness or the city. An estimated ten percent of the adult population (and sixteen percent of youth) experiences a strong fear or avoidance reaction to a specific thing or situation that is significantly out of proportion to the actual risk posed. Common phobias include heights, snakes, spiders, elevators, confined spaces, germs, flying, or the dark. Less common phobias I have seen clinically include fish and “small soft things, like rabbits”. However, the object of a phobia may be almost anything. A table below, borrowed from the MHWFA course book, lists 17 different phobia examples which you can try matching up to their correct meanings (answers at the end of the article).

Supporting a Person With Specific Phobia in the Wilderness Take a Deep Breath If you forget everything else, take a deep breath and settle your own nervous system. While I immediately tensed up at Gabrielle’s reaction and wanted to run to her, I tapped in to a thankfully ingrained habit of taking a deep breath, and (heart still pounding) walking to her side. Being around someone who is experiencing phobic response can activate your own fight / flight / freeze system. On the contrary, you providing a calm, nonanxious presence activates the other person’s mirror neurons and naturally will help them to regulate their own emotional responses in a healthy way. Awareness How grateful I was to have had a heads up about Gabrielle’s phobia from her medical form before our expedition began! Although most registration forms ask only about physical health concerns, it is equally invaluable to attune to mental health issues that may arise in the field. Consider incorporating questions from the MHWFA pre-trip mental health form (a free resource available on our website) in to the registration forms for your own organization. Intervention Strategies Plan ahead: when a phobic stimulus is encountered in the field, what strategies will help manage it in the moment? The person may already have their own ideas and strategies established, which you can build on. Diaphragmatic breathing, mindfulness, and tapping are three of my favourite and most effective interventions. When you encounter a phobic stimulus, immediately tune in to and name out loud some of the other simple things you can see, hear, feel, smell, and/or taste around you. Or, try pairing deep “belly breathing” with a gentle, consistent tap on the collarbone, eyebrow, or anywhere else that feels grounding. We can also gently identify and challenge unhealthy, unrealistic cognitions that accompany phobias. Someone with a specific fear of bridges may experience an intrusive thought that “the bridge will collapse as I cross it.” Assuming that the bridge really is solid, of course, a healthy, realistic alternative thought might become a simple self-reminder to repeat: “I am grateful for the strength of this bridge and the skill and care of those who constructed it.” All of these intervention strategies can be incorporated in to a safety plan, which is another free resource available on our website for supporters as well as clients.

Be Aware of Flooding “No thanks; I’m definitely not going to look at a picture of a snake if I don’t have to,” Gabrielle might have said. Would it have been helpful for me to insist? Baby Step Ladders do include risk and must be used cautiously. Flooding may occur if someone is exposed, even voluntarily, to too much of a stimulus too quickly, and the result can be an exacerbated phobic response going forward. Not helpful! If you are considering a Baby Step Ladder, it is wise to both 1) follow the motivation of the client in whether to do so, and 2) have additional support or training in this area (e.g. a self-paced workbook like the Bourne (2015) resource cited below, or training offered by a MHWFA course). Connecting to Resources In the field, we’re doing first aid. Help this person additionally connect to a resource that can support them in ways that they choose in the medium-to-long-term. Some clinicians excel in particular areas; one therapist I saw in Victoria specializes in phobic responses, calling himself the “Fear Doctor”! Other supportive resource options may include a mental health line, physician, counsellor or perhaps an attuned spiritual leader in their community.

1 Comment

Collin H.

8/30/2021 02:13:06 pm

Thank you for sharing this valuable and priceless knowledge with us. Being aware of of different phobias that can (and certainly do) occur in the field and different strategies and tools to help people through is vital information.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Details

AuthorDaye Cooper Hagel is a clinical counsellor, veteran wilderness guide, and director of the Mental Health Wilderness First Aid program on the west coast of British Columbia, Canada. Read more about her and the MHWFA on the About Us page! Archives

July 2022

Categories |

About Us |

Courses & Events |

|

|

We do not require personal medical information from our students, volunteers,

staff, or contractors as a condition of providing services. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed